President Trump issued an executive order on June 21 that laid out a plan to…

Un

SWA Job Order California: What is an EDD Number?

What is an EDD Number? An EDD Number is technically the state unemployment insurance identification number that the Employment Development Department of California issues a company. Here’s a visual example from the UI Online FAQ: How do I register for an EDD Number? To register for an EDD Number (in California) use this link: https://www.edd.ca.gov/payroll_taxes/e-Services_for_Business.htm,

What is an EDD Number?

An EDD Number is technically the state unemployment insurance identification number that the Employment Development Department of California issues a company.

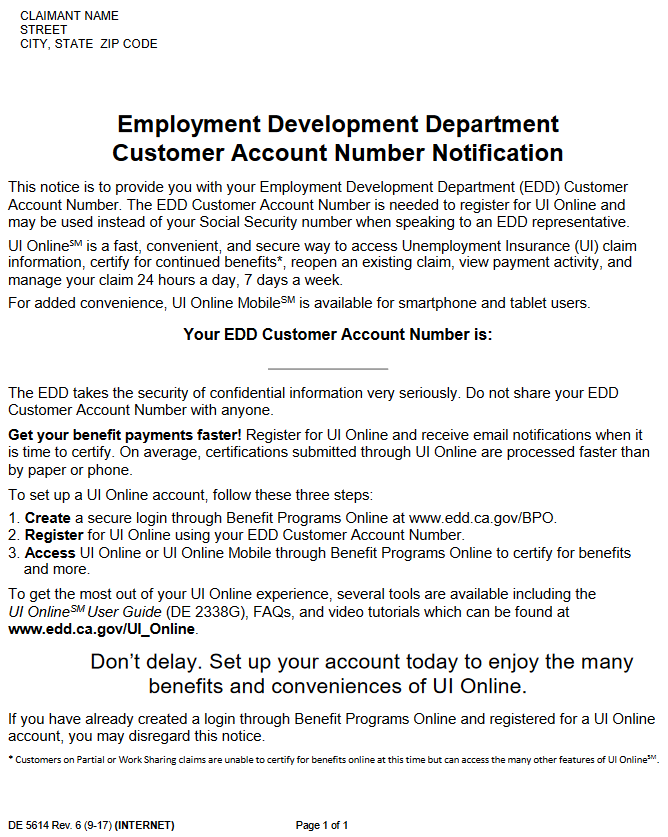

Here’s a visual example from the UI Online FAQ:

How do I register for an EDD Number?

To register for an EDD Number (in California) use this link: https://www.edd.ca.gov/payroll_taxes/e-Services_for_Business.htm

The EDD Number form will look like this when you receive it. (see below image)

It’s on a form known as DE-5614. Click here for a PDF sample: https://www.edd.ca.gov/pdf_pub_ctr/de5614.pdf

How do I find my company’s EDD Number?

Per the EDD do as follows:

All Unemployment Insurance customers who file a new claim will automatically receive their Employment Development Department (EDD) Customer Account Number (DE 5614) letter within 10 business days of filing.

If you have lost, misplaced, or never received your EDD Customer Account Number, contact the EDD:

Online: Go to Ask EDD and select the category Unemployment Insurance Benefits, the sub category UI Online, and the topic EDD Customer Account Number. Select Continue at the bottom of the page to begin the process of submitting your message.

By Phone: Call 1-800-300-5616 from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. (Pacific time), seven days a week.

Why do I need an EDD Number for PERM Recruitment?

What else can I use my EDD Number for?

UI Online

Register for UI Online

CalJobs Registration

,

Un

FLAG.DOL.GOV: Essential Resource for PERM Labor Certification Recruitment Compliance

The Foreign Labor Application Gateway (FLAG) at https://flag.dol.gov/ serves as the Department of Labor’s comprehensive digital portal for employers seeking to hire foreign workers through various employment-based immigration programs. For employers navigating the complex PERM Labor Certification process, FLAG has become an indispensable tool that streamlines compliance with recruitment advertising requirements outlined in 20 CFR,

The Foreign Labor Application Gateway (FLAG) at https://flag.dol.gov/ serves as the Department of Labor’s comprehensive digital portal for employers seeking to hire foreign workers through various employment-based immigration programs. For employers navigating the complex PERM Labor Certification process, FLAG has become an indispensable tool that streamlines compliance with recruitment advertising requirements outlined in 20 CFR 656.17.

When conducting PERM recruitment activities, employers must meticulously document their good faith efforts to recruit U.S. workers before hiring foreign talent. FLAG integrates seamlessly with these requirements by providing a centralized platform to submit, track, and manage labor certification applications. The system specifically supports employers in demonstrating compliance with mandatory recruitment steps, including the placement of job orders with State Workforce Agencies, professional journal advertisements, and additional recruitment activities as specified under 20 CFR 656.17(e). By utilizing FLAG, employers can ensure their recruitment efforts align with Department of Labor standards, potentially reducing the risk of audit or denial during the PERM certification process.

PERM Recruitment Requirements and FLAG Integration

FLAG’s role in the PERM process becomes particularly valuable when addressing the specific recruitment documentation requirements of 20 CFR 656.17. The regulation mandates that employers conduct recruitment steps within 180 days of filing, including two Sunday newspaper advertisements, a 30-day job order with the State Workforce Agency, and three additional recruitment activities from a designated list. FLAG not only facilitates the proper filing of these recruitment efforts but also helps employers maintain the required recruitment report detailing lawful job-related reasons for rejecting U.S. applicants.

Recent updates to FLAG have enhanced its functionality for PERM applications, allowing employers to more efficiently upload supporting documentation, track prevailing wage determinations, and monitor case status in real-time. For immigration attorneys and HR professionals managing PERM cases, FLAG’s user interface provides critical visibility into the certification process, helping ensure that all regulatory requirements are met before and during the application period. As labor certification requirements continue to evolve, FLAG remains the authoritative platform for employers seeking to navigate PERM recruitment compliance successfully.

,

Un

THE H1B GUY NEWS (12/3/2021) H1B in Decline and Documented Dreamers in Limbo

The H1B Guy News for the week ending December 3, 2021.

Topics:

H1B in Decline

Documented Dreamers in Limbo

The Number of Immigrant Workers With H1-B Visas Drops the Most in a Decade

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articl…

Ross, Padilla Lead 49 Colleagues in Urging DHS to Expand DACA Eligibility to Documented Dreamers

https://ross.house.gov/media/press-re…

Read the full post

Subscribe to The H1B Guy Podcast

Join The H1B Guy Channel and Chat on Telegram

Follow The H1B Guy on Twitter

Enforcement / ICE / DHS

USCIS Allows I-765 NOA Approval Receipt Notice to Establish I-9 Employment Verification

We have great news for our readers. On August 19, 2020, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) issued an important announcement for applicants whose Form I-765 Application for Employment Authorization has been approved, but who have not yet received their employment authorization document (EAD card) by mail. What’s this all about Since the,

We have great news for our readers. On August 19, 2020, the

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services(USCIS) issued an important announcement for applicants whose Form I-765 Application for Employment Authorization has been approved, but who have not yet received their employment authorization document (EAD card) by mail.

What’s this all about

Since the emergence of the Coronavirus outbreak, there has been significant delays affecting the production of certain Employment Authorization Documents also known as EAD cards, which permit an applicant to obtain lawful employment in the United States, a driver’s license, and other important documentation such as a Social Security number.

These delays have caused hardships for applicants and created additional obstacles to finding employment during an already difficult economic time.

The good news is that USCIS is providing temporary relief for applicants who have received an approval notice, but have not yet received an employment authorization document (EAD card) in the mail.

Due to the unprecedented and extraordinary circumstances caused by COVID-19, USCIS will allow foreign nationals to temporarily use their Form I-797 Notice of Action, with a notice date on or after December 1, 2019 through August 20, 2020, informing the applicant of the approval of their I-765 Application for Employment Authorization, as evidence of Form I-9, Employment Eligibility Verification.

In other words, individuals can now provide employers with the I-797 Notice of Action, receipt of approval of the Form I-765 Application for Employment Authorization, in order to qualify for lawful employment.

Pursuant to the announcement, the Notice of Action is now considered a List C #7 approved document that establishes employment authorization issued by the Department of Homeland Security, even though the Notice states that it is not evidence of employment authorization.

Accordingly, employees can present Form I-797 Notice of Action showing approval of their I-765 application as a list C document for Form I-9 compliance until December 1, 2020.

For I-9 completion, employees who present a Form I-797 Notice of Action described above for new employment must also present their employer with an acceptable List B document that establishes identity. The Lists of Acceptable Documents is on Form I-9. Current employees who require reverification can present Form I-797 Notice of Action as proof of employment authorization under List C.

We believe this is a step in the right direction and hope that USCIS can quickly and efficiently resolve the EAD backlogs as soon as possible.

For more information on acceptable documentation for verifying employment authorization and identity please click here.

Source: USCIS Allows I-765 NOA Approval Receipt Notice to Establish I-9 Employment Verification

,

-

Un5 years ago

Un5 years agoPERM Process Flow Chart

-

Enforcement News15 years ago

Enforcement News15 years agoFake ID Makers Arrested In Dallas

-

BREAKING5 years ago

BREAKING5 years agoPERM Recruitment Advertising, How It Works.

-

Today's News13 years ago

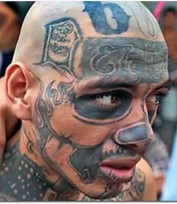

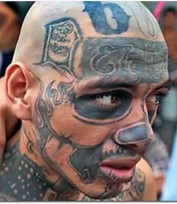

Today's News13 years agoImmigration: Gangster Tats = Visa Denied

-

BREAKING5 years ago

BREAKING5 years agoUSCIS Statement Throws Constitution Out the Window

-

BREAKING4 years ago

BREAKING4 years agoDeSantis parts with Trump in response to Surfside tragedy

-

BREAKING4 years ago

BREAKING4 years agoTrump heads to U.S.-Mexico border to attack Biden policies

-

BREAKING4 years ago

BREAKING4 years agoBiden administration settles with spouses of immigrant visa holders, clearing them for work